Coaches Find Well-Paid Niche in Fast-Paced Lives

February 19, 2001

By Jacqueline L. Salmon

This time last year, Gary Earle hated his life. The miserable winter cold. Washington's maddening traffic. A disappointing new job.

Finally, the Reston commercial real estate executive took a step he never dreamed he would: He hired a "personal coach" to help him dig out of his rut.

Cut through the 2024 election noise. Get The Campaign Moment newsletter.

For two months, he took personality tests, researched professions and meditated with coach Anne Griffin, of Rockville, in a candlelit room in an attempt to visualize his ideal life. Today, he and his wife, Carmen, live in a small town in Northern California's wine country where he happily runs his own executive-search firm.

"I ended up finding everything I wanted," said Earle, 49, giving Griffin much of the credit. "It was a great process for me."

Combine a career counselor, a therapist, a best friend and a personal trainer, add New Age spirituality and a bit of the nagging mom, and you've got today's personal coach -- a profession that's growing almost by the day. In this area alone, several hundred have set up shop recently, coaching their way to money and success by helping you tackle your personal demons.

Feeling fat? Randi Wortman, of Rockville, is a "positive body image" coach. Want help planning your sunset years? Fontelle Gilbert, of Springfield, is a "retirement and adult transition" coach. Need some direction? Dottie Perlman, of Potomac, is a "life purpose" coach, while Cherryl Neill, of the District, is a "success" coach. How about the bigger picture? Stephen Poplin, of Bethesda, is a "spiritual" coach.

Or -- and don't we all wish we had this problem? -- maybe you need help investing that first million? Catherine Franz, of Arlington, is a "millionaire" coach. You make it, she'll help you figure out what do with it.

"Nowadays," Neill said, "everybody's a coach."

An Open Field Burned-out lawyers, accountants, hypnotists, career counselors and homemakers are among those now charging $100 and up an hour to help put you on the road to satisfaction. Therapists, eager to escape managed-care restrictions and attracted by the ready supply of highly motivated clients who pay out of their own pocket, also are remaking themselves into personal coaches.

"It helps us do what we've always done, which is to help good people make transformative changes in their lives, but without the interference of the health-care dollars," said Ben Dean, a Bethesda therapist who has trained 350 colleagues as personal coaches in his three-year-old program, coachmentor.com. The business "has been exploding," Dean said. "I'm adding staff. I'm doing workshops all over the country."

Membership in the six-year-old International Coach Federation, the largest such group in the nation, has doubled annually and now stands at 4,000, said President D.J. Mitsch. That total vastly understates the number of people with coaching businesses, Mitsch said. His group has chapters in 36 countries.

Some personal coaches specialize in assisting adults with attention deficit or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In Ohio, coaches are working with prison inmates.

Proponents say coaching is more suited to today's rush-rush lifestyle than past self-improvement methods that moved in and out of vogue.

"We live in a microwave world, where one-hour weekly coaching makes a lot more sense than workshops, shrinks and reading," said Caela Farren, whose Annandale consulting business, MasteryWorks, offers coaching. "It's on your calendar, the time seems doable, and you are very clear about what you want or need to learn."

That's not to say coaching doesn't have its naysayers: Plenty of people both inside and outside say it's luring too many unqualified enthusiasts. With no licensing or state-required credentials, anyone can set up shop and start charging hefty fees.

"It concerns me," said Mitsch, of the International Coach Federation. "There are people calling themselves coaches who haven't had any training."

Coaching the Coaches "I am the power!"

The 75 or so people crowded into the meeting room at a Sheraton in Richmond stand and belt out the words under the direction of Joshua Bloom.

"Let's try that one more time," encourages Bloom, 32, a perky former children's songwriter who has been a personal coach for two years. "But this time . . . I want you to be creative and find your own movement."

"I AM the power!" the crowd roars back, some in the audience flinging their arms wide and kicking out their feet.

This get-together in early February is the inaugural meeting of the Coach Federation's Virginia chapter, and turnout is about double what had been expected.

When organizer Tom Davidson asks for a show of hands of those who have been coaches for less than a year, about a third of the room responds.

"Wow!" Davidson says. "All of us are pretty new at this."

For the next two days, they will chant, stretch, meet and network. They will learn "deep and spacious listening," how to develop a great telephone voice, and ways to build their coaching practice.

Susan Pritchett Post, a corporate banker for 20 years, has been on the personal-coaching circuit for the last year.

"I wanted to find something that was intellectually stimulating, reasonably well paid and flexible," says Post, 51, of Alexandria. "And also [something] that makes my heart sing -- and this is it."

The cost of hiring a coach doesn't seem to deter clients.

"I thought money would be a problem, but a lot of people spend money on personal training [and] dating," says Kevin Donaleski, 47, a former Marine who now works for an engineering firm and coaches on the side. "They're willing to spend money to make a change."

Indeed, fees help people stay focused on their goals, say coaches, many of whom ask clients to sign a three-month contract.

"My clients are paying me a good amount of money to help get them to where they want to go," Bloom says. "Once people have put down the money to pay me, then they make a decision that they're not going to stay the same way. . . . The money is really a good stick."

No One Standard In an effort to impose some limits on the gold rush, the coaching federation established a credentialing program in 1998, requiring coaches to supply references, complete a training program certified by the federation and have a minimum of 750 hours of coaching experience.

But of the 38 "coaching universities" that have sprung up across the country -- offering training for fees of about $5,000 -- just eight offer the accredited program, federation officials say. And so far, only about 600 people have obtained credentials.

Four-year colleges are also setting up programs -- George Washington, Georgetown and George Mason universities, among them -- although these are tailored for corporate coaching.

"In some ways, that's our greatest concern within the community of people who take [coaching] seriously and see it as a distinct method for helping people," said Alan Shusterman, who co-heads Insight Associations, a Potomac firm that does personal and corporate coaching. "Everybody's calling themselves a coach, and it's getting very muddled as far as what a coach is."

Experienced coaches -- and that's a relative term in this emerging field -- say they focus on helping people define what they want in specific areas and then keep them zeroed in on their goals.

Weekly assignments are common. So are telephone and e-mail sessions for busy professionals. Lengthy discussions of family dysfunctions are not.

Facing the Homework On a recent Friday, Bethesda coach Marcia Girardi held her regular half-hour phone session with Michelle La Perriere, a Baltimore artist and teacher who has been consulting with Girardi since September in an effort to better balance her life.

"I've had a lot of good but painful moments," La Perriere, 41, told Girardi as they discussed the previous week. For homework, Girardi had asked La Perriere to stock her desk with healthy foods and get eight hours of sleep each night, keeping a written record of how she did. After initial progress, La Perriere said, she'd been slipping. Tearfully, she listed her many obligations.

Girardi, 50, a former graphics consultant who has been coaching for 2 1/2 years, agreed that La Perriere needed to get back on track but looked at the positive side. "You have so much to offer," she said. "You are such a great support to people."

When La Perriere veered briefly into a monologue about her childhood, Girardi quickly steered her back to the present.

After a visualization in which La Perriere took herself out of what Girardi has dubbed her "harried waitress mode" and imagined herself as a graceful creature who "makes each moment precious," Girardi wound things up. The two worked out a list of tasks for the coming week. Girardi suggested that La Perriere take a full day off for herself, but she doubted she could, so they compromised.

"I'm going to go to a cafe and have a large cappuccino," La Perriere said, "and maybe write some cards."

No, said Girardi, no cards. Do nothing.

La Perriere groaned. "God," she said, "it's so ingrained."

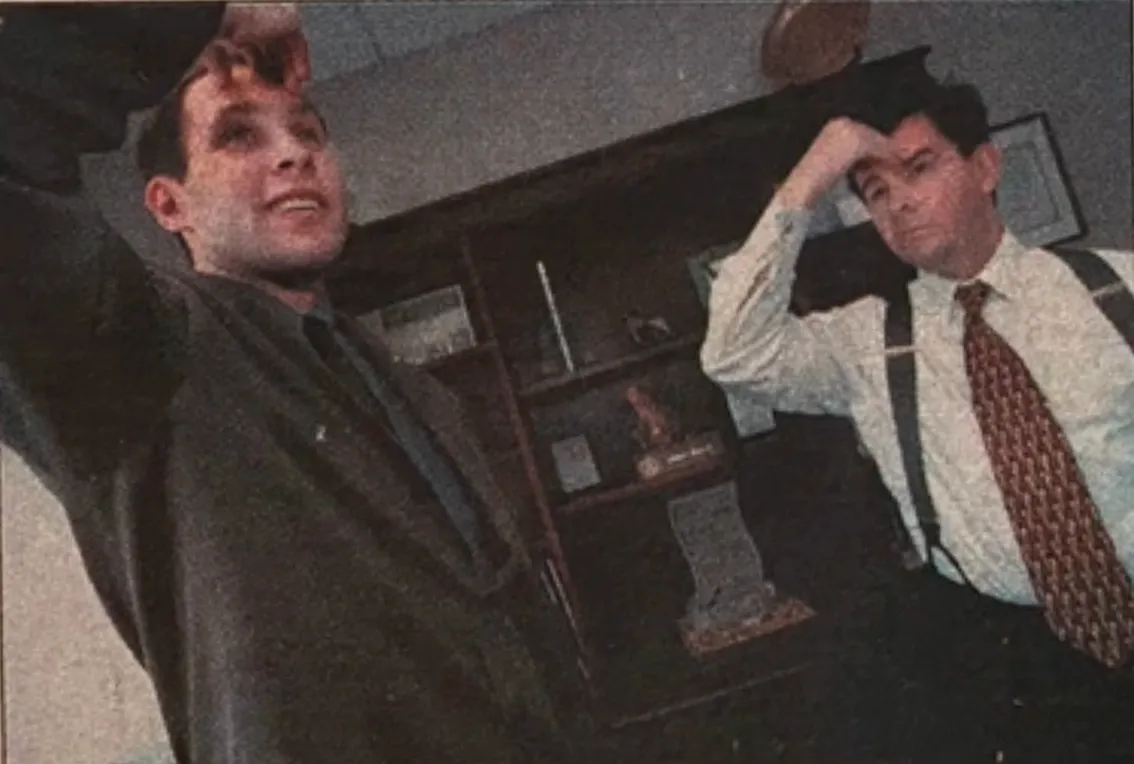

Personal coach Joshua Bloom, left, works with Bill Moran in Moran's office at Merrill Lynch, where Moran is a senior financial consultant.Bill Moran during a session with Joshua Bloom, who said clients pay him "a good amount of money to help get them to where they want to go.